New 2023 Data on Union Membership and Finances

Finance Unionism is alive and well, but the UAW is showing the path forward

The 2023 membership and financial data for individual U.S. unions are now available from the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS). Which unions gained membership, and which unions lost membership? What are the long-term trends for each union since 2010? What is the relationship between membership growth (or decline) and the balance sheet of America’s largest unions? How much money do union headquarters have to invest in strikes and organizing? I’ll try to tell the story with a collection of charts and tables, but first, let’s look at the data from a bird’s eye view.

Membership Decline and Finance Unionism

Each year, the DOL’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases a report on union membership trends based on the Census Current Population Survey (CPS). As I wrote a few months ago, the report showed that union membership edged up 135,000 in 2023, but union density — the percentage of workers who were members of unions — declined to 10%, the lowest number on record. For reference, in 2010 union density was 11.9%.

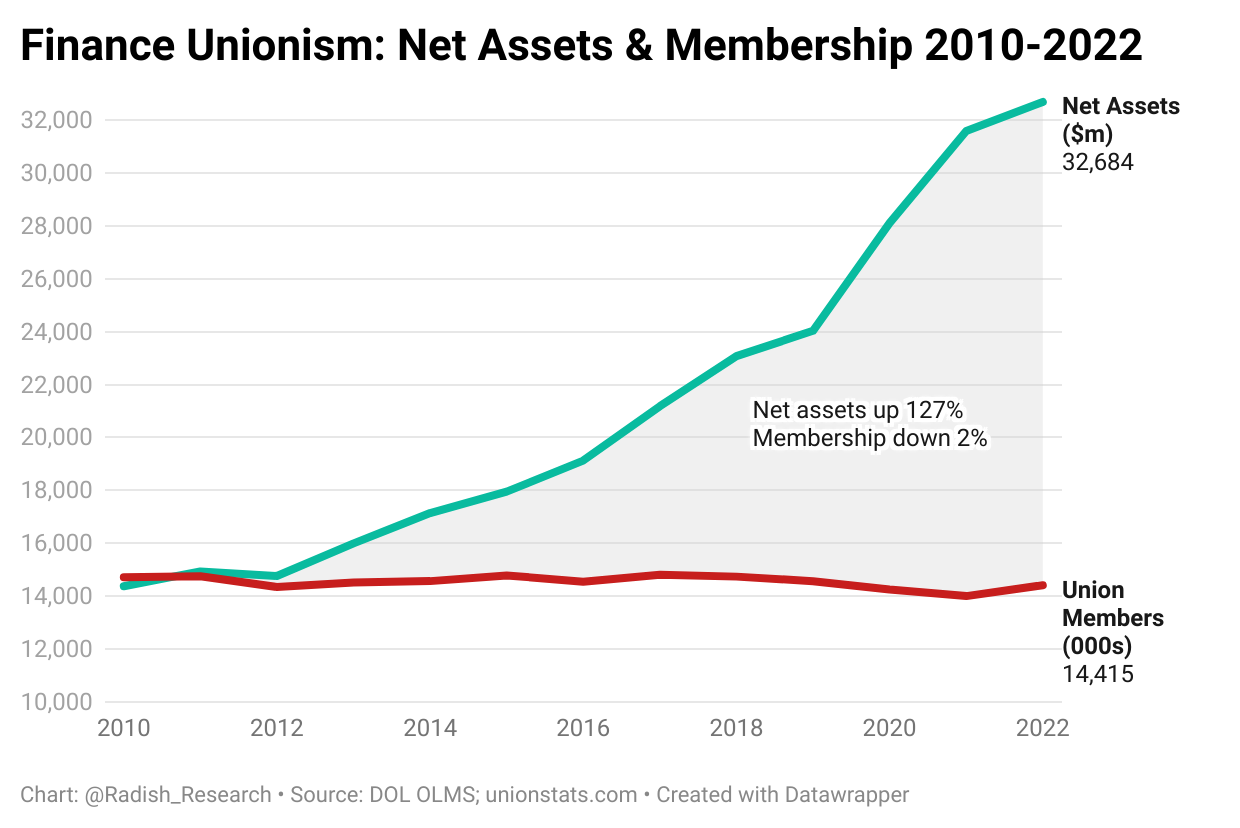

While union density and membership steadily decline, labor’s net assets (assets minus liabilities) are increasing, a phenomenon I call Finance Unionism. Since 2010, labor's net assets have increased from $14.4 billion to $32.7 billion in 2022, or 127%.

The tables and charts below summarize these membership and finance trends for the largest U.S. unions. One caveat is that membership growth (or decline) is an imperfect proxy for new organizing. Membership at a union can increase without substantial new organizing because, for example, the union has collective-bargaining agreements in growing sectors of the economy (and vice versa). The Teamsters have gained tens of thousands of new members at UPS because the company has rapidly grown over the last few decades (while FedEx and Amazon remain unorganized).

Seth Harris at the Power at Work Blog wrote an excellent article breaking down the various organizing strategies that lead to membership growth, and it is worth reading to get behind the membership numbers. In addition to the factors outlined by Harris, membership at a union can increase due to mergers and affiliations with other unions, which doesn’t increase the overall number of organized workers. This is all to say that the membership numbers need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Nevertheless, membership growth is a crucial indicator of labor’s resurgence (or decline) and one measure of the effectiveness of individual unions. Similarly, looking at a union's balance sheet gives a very rough idea of its strategic posture: Is a union investing in organizing and strikes or using dues to accumulate financial assets?

Who Grew in 2023?

I analyzed the filings for the top 20 largest U.S. unions ranked by membership. Some unions include retirees in their membership numbers (e.g., the NEA includes 322,946 retirees in 2023), while many others do not. To enable apple-to-apple comparisons, I subtracted the retirees from the membership numbers of all unions.

Table 1 shows the top unions ranked by absolute growth in membership from 2022 to 2023 (click on any table in this report to sort by categories). SEIU, which has a long-standing and aggressive organizing program, sits at the top of the list, adding nearly 32,000 members. Interestingly, two smaller unions – the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) and the Machinists – saw a substantial increase in membership, eclipsing the far larger Teamsters’ union.

Table 1

The significant membership decrease at the Laborers is deceiving because it was primarily driven by a reduction in non-voting associate members at the affiliated Mail Handlers union, not a decrease in the “regular” membership.

Table 2, showing the percentage increase in membership from 2022, gives a little more context on how unions are growing in relation to their membership base. Again, the smaller unions are growing at faster rates than many larger unions.

Table 2

Overall, membership in the top 20 unions increased by 134,000 in 2023, consistent with the DOL's annual membership survey, which showed a 139,000 increase in 2023. Although these methodologies for determining union membership differ, the results are similar.

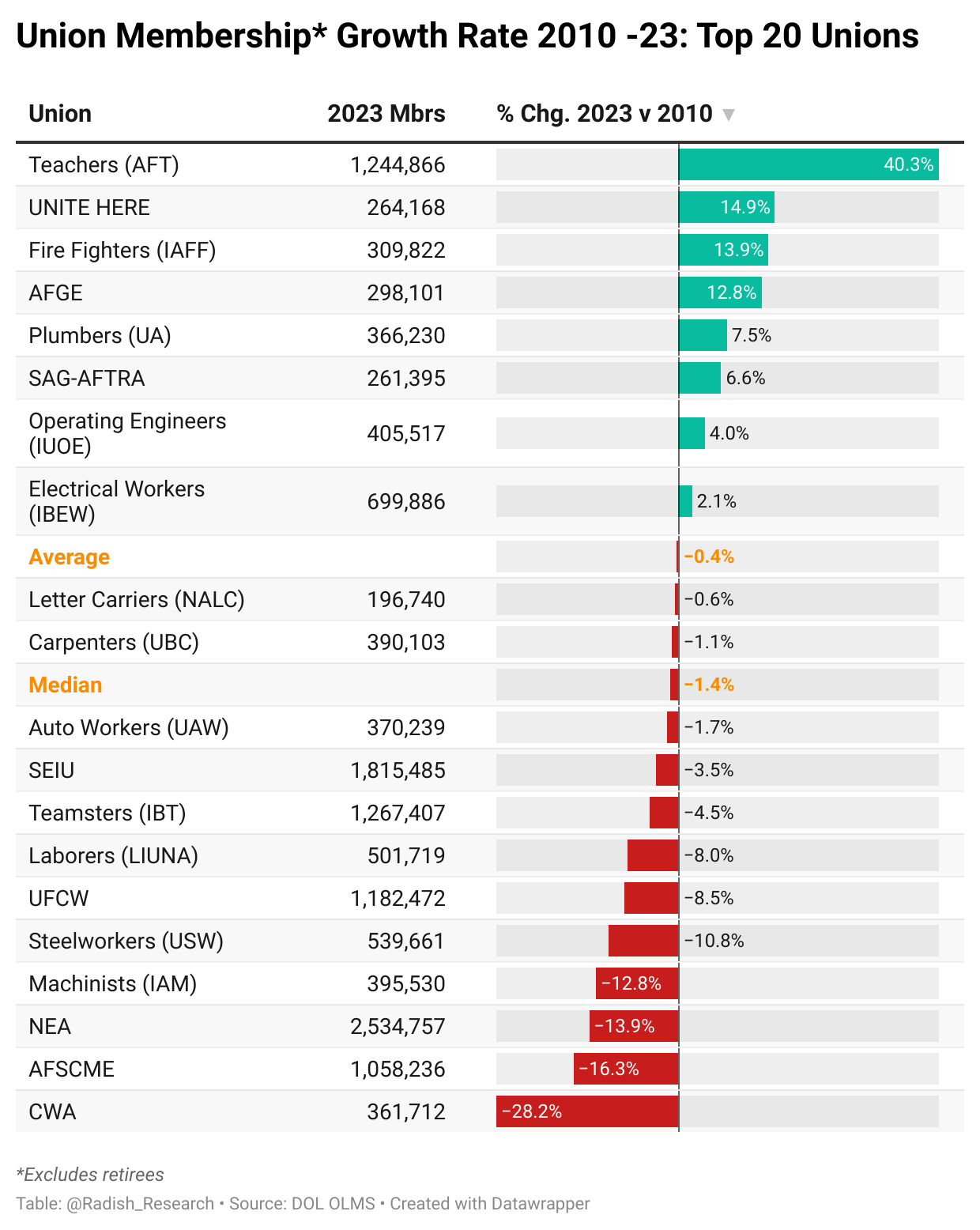

Long-Term Membership Trends: 2010-2023

What are the long-term membership trends for the largest U.S. unions? Unlike the 2023 to 2022 comparison, Table 3 shows far more red bars of membership decline. Only eight of the top twenty unions saw membership growth since 2010, while the remainder saw net membership losses.

Table 3

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) saw a considerable increase in membership, but this is misleading. Merged local and state members accounted for nearly half of the increase. In addition, the AFT has an alphabet soup of eleven membership categories that have not been consistent since 2010. The full-time (and largest) membership category has increased by 11,434 since 2010.1

The Firefighters (IAFF), AFGE, and UNITE HERE saw impressive gains. As a former UNITE HERE and Culinary Union 226 staffer, I’m biased, but I am astonished that UNITE HERE came back from losing half its membership during the pandemic to show a net gain since 2010.

Table 4 shows the percentage change in membership since 2010. Given the Janus decision and the general attack on public sector unions, it is unsurprising that NEA, AFSCME, and CWA lead the list in membership decline percentage.

Table 4

Union Membership “Market Share”

So, what percentage of the total union membership in the U.S. does each union represent? As Table 5 shows, union membership is highly concentrated: the top five unions represent 50% of union members (or 8.0 million), and the top ten represent 70% (or 11.3 million).2

Table 5

This table has some limitations. First, several international unions represent a sizable number of members in Canada, but the DOL or Canadian regulators do not require unions to break out the numbers by country (the table above highlights unions in red with sizeable Canadian membership). Thus, the percentage of U.S. membership will be slightly inflated for the unions with Canadian membership.

Second, unions have a fair amount of flexibility in defining membership categories. For example, the AFL-CIO claims it has thirteen million members, but four million of those “members” are from Working America. The AFL-CIO set up Working America in 2003 to contact non-union workers in political campaigns (this was before the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, which allowed unfettered spending by unions and others). “Members” of Working America do not have collective-bargaining contracts, voting rights, or mandatory dues. You can basically join by clicking on a link. Some other unions also have similar membership-lite categories.

Finally, unions typically do not count newly organized members who have yet to obtain their first contract (this practice is specified in each union’s constitution). For example, the 10,000 members of Starbucks Workers United are not included in SEIU’s total membership number.

Despite the limitations of the data, the rough approximation shows that existing union membership is highly concentrated in the top ten unions. However, it is important to remember that membership can be decentralized within each union, geographically dispersed among hundreds of local and regional bodies. For example, the Steelworker’s 539,000 members are dispersed among 1,800 locals. And there are nearly 15,000 individual union entities that file reports with the Department of Labor annually.

Finance Unionism and Net Assets

While union membership continues to decline, union treasuries are growing exponentially. I call this “Finance Unionism,” a practice where union leaders focus on accumulating financial assets rather than investing those resources in mass organizing and strike activity. For a detailed analysis and methodology, please see my report, Labor’s Fortress of Finance: A Financial Analysis of Organized Labor and Sketches for an Alternative Future: 2010-2021.

Table 6

As Table 6 shows, union membership has declined by 2% since 2010, but net assets (assets minus liabilities) have increased from $14.4 billion to $32.7 billion in 2022, or a 127% increase (2023 data is not fully available yet). Unions have been able to do this because they run large budget surpluses, spending less on strikes and organizing than they receive in member revenues and investment income.

The breakdown of total union spending in Table 7 gives a good idea of labor's strategic posture (i.e., Finance Unionism). Since 2010, unions have spent less than $1 billion on strike benefits, compared to $30.1 billion in benefits for staff and officers and $9 billion on politics.

Table 7

What does the balance sheet look like for each union? As Table 8 shows, nearly every large union saw their net assets increase since 2010, with the median union showing a 137% increase in net assets. The only union that saw a decrease was UNITE HERE (a small $400,000 drop).3

Table 8

Since 2010, the net assets of the top twenty union headquarters grew from $3.2 billion in 2010 to $8.5 billion in 2023, or a 164% increase. This understates the massive growth in net assets because two-thirds of union assets are located at the local level, not at the headquarters level.

As Table 9 shows, every union with a decline in membership has seen an increase in their net assets since 2010. Interestingly, UNITE HERE has increased membership by 15% since 2010, but net assets have decreased by less than a percent. Perhaps one reason is that the union spends up to 50% of its budget on organizing, investing in workers rather than financial assets.

Table 9

How is it possible for nearly all unions to grow assets while losing dues-paying members? First, membership dues are typically tied to a percentage of wages, so as union wages rise, membership dues also rise, softening the financial impact of declining membership. Second, labor generates significant investment and rental income from its growing balance sheet, including investments in the stock market (and even private equity and hedge funds).

Although unions have significant net assets, these assets are not distributed equally. As Table 10 illustrates, there is a wide disparity among unions, ranging from $3,060 in net assets per member at the UAW to a low of just $38 per member at the AFT. Net assets are highly concentrated in the manufacturing unions and building trades, while unions in the service and public sector generally have the fewest net assets per member.

However, remember that this data only covers net assets at the headquarters level. Many unions have significant assets at the local and regional level, and that will be addressed in a future report.

Table 10

The UAW and Beyond Finance Unionism

The Auto Workers (UAW) provide an alternative model to the widespread practice of Finance Unionism. After Shawn Fain was elected UAW president in early 2023 in the first direct election of officers by the membership (as well as a newly elected Executive Board), the union dramatically increased spending by $181 million in 2023 or a 70% increase. According to financial filings with the DOL, the spending increase was primarily driven by a $152 million expenditure on strike benefits for members in the historic Stand-Up Strike at the Big 3 automakers (and other strikes), as well as increases in spending on representational activities and benefits.4

Table 11

Following the stunning success of the Stand Up Strike, the UAW promptly announced $40 million in new organizing funds to support non-union autoworkers and battery workers organizing across the country, particularly in the South. Two months later, the UAW won an election to represent over 4,300 auto workers at Volkswagen, the first successful unionization vote at an auto factory in the South. In May, another 5,200 auto workers will have the opportunity to vote for union representation at a Mercedes-Benz plant in Alabama.

Instead of stockpiling financial assets, the UAW is (finally!) investing in high-visibility strikes and ambitious organizing programs that are capturing the imagination of workers throughout the world. Hopefully the rest of the labor movement is paying close attention, willing to take off their golden handcuffs and make a financial and strategic bet on the working class.

Spending more is not an automatic recipe for success (and who hasn’t worked on expensive campaigns that failed?), but strikes and organizing campaigns require significant financial resources. Far too many unions invest these resources in the financial markets rather than in workers. In my view, a concrete sign of labor’s resurgence will be reflected in the financial statements: when net assets decline rather than grow and when billion-dollar surpluses turn to deficits—this will signal that unions are finally investing in organizing and aggressively engaging in strikes and other militant activities.

For an interesting account of AFT’s membership categories, see https://www.the74million.org/article/union-report-in-the-byzantine-world-of-american-federation-of-teachers-membership-numbers-just-dont-add-up/. I disagree with the politics of this website and author, but it is a solid analysis of the data.

The Census Bureau asks two questions regarding membership: “are you a member of a labor union?” (14.4 million workers said “yes” in 2023) and “are you covered by a union?” (16.2 million workers said “yes” in 2023). For this report, I am using the larger covered number to adjust for some of the inflated individual union membership numbers (for example, Canadian membership).

NA = SAG and AFTRA merged in 2012 so 2010 data is not available. The Firefighters only had $40,000 in 2010 (growing to $46 million in 2023) so the percentage increase would render the chart unreadable.

The DOL defines “representational” spending as direct and indirect expenditures for “the negotiation of collective bargaining agreements and the administration and enforcement of the agreements made by the labor organization…[and] associated with efforts to become the exclusive bargaining representative for any unit of employees, or to keep from losing a unit in a decertification election or to another labor organization.”