Welcome to the first edition of the Radish Research newsletter!

Recently C.M. Lewis – a union activist and staff representative who writes (and tweets) frequently on union strategy and tactics – wrote an article responding to my report on labor finances (as well as an article about the report by Hamilton Nolan). I am grateful for the time and effort Lewis put into analyzing the report, and excited that it has helped spur debate about union priorities and strategy in this moment of opportunity for unions and the working class.

In his review, Lewis raises a number of methodological issues and argues that there are significantly less assets available for organizing and other union initiatives than the data analysis suggests, primarily because of “restricted” union assets devoted to strike funds. He concludes that while there may be “some amount of resources exist that could be tapped to fund additional organizing,” those assets should be subject to democratic decision-making and not “centralized diktat.”

I will first respond to his warnings about union democracy, then address the methodological concerns in detail below.

Member Democracy

Lewis writes that the “institutionalist approach” in the report “obscures the reality that unions both are and should remain membership based organizations with varying degrees of direction-setting and resource prioritization determined by democratic mechanisms.” In addition, Lewis claims that the financial analysis implies “top-down decision-making” and a “centralized diktat.”

Perhaps the confusion here is conflating the method of analysis (i.e., looking at union finances and initiatives from a macro level) with the political practice of union strategy (i.e., how democratic movements and factions within labor achieve their programmatic aims). The report notes that organized labor can and should spend substantially more on union initiatives, but there is nothing in the report that advocates that this should be done through the undemocratic imposition of top-down decision-making, or the abolition of union democracy. To the contrary, the report concludes that change will not come from “leaders at the top” but from the broad reform movements of workers seeking to democratically challenge an entrenched labor leadership. My governing assumption, one that I didn’t think I needed to explicitly state, is that all union assets should be subject to democratic control.

Lewis also seems to suggest that because unions are (formally) democratic — and union finances are subject to democratic control — that criticizing the financial practices of unions is, well, undemocratic. I have a less sanguine view of the current state of union democracy and whether the key strategic decisions of unions (especially finance and budget decisions) are reflective of a robust democratic process by the membership. Unions are formally democratic (by law), but still have a long way to go to reach substantive democracy in practice. For example, Jonah Furman, in his excellent Jacobin article How Democratic Are American Unions?, raises a number of questions about the practice of union democracy.

Although Lewis asserts that any “inadequate member democracy” in unions will automatically lead to reform movements of the membership, it is worth remembering that the reform movements at the UAW and Teamsters were only able to gain greater power because their unions were so corrupted and undemocratic that the federal government and courts branded them as criminal enterprises, installing government monitors over the operation of the unions. Unions should be working to radically expand member democracy now and avoid at all costs additional government takeovers because of poor democratic practices.

Rather than reflective of member democracy as Lewis writes, the report theorizes that the financial practices of many unions are due to the control of key decision-making by an entrenched and highly-compensated labor leadership elite that is economically aligned with the current system. Using Census data, the report shows that while unions have reduced essential staff positions, management positions within organized labor have increased by 28% since 2010, with the top leaders and senior management earning incomes in the top tenth percentile of income in the U.S. And the report concludes that the spending practices of unions will only change when a broad array of worker and member reform movements challenge this top-heavy control.

A debate about union democracy is perhaps a discussion for another day, but casually suggesting that I endorse an anti-democratic strategy is a very serious charge, and I take it seriously.

Strike Funds (aka “Functionally Restricted Financial Reserves”)

Lewis questions the amount of union assets that are devoted to strike funds (formally and informally), suggesting that a “significant percent” of union assets are “restricted” and unavailable for other objectives like devoting more resources to organizing. And Lewis cautions that these strike funds shouldn’t be “extensively raided for other uses.”

Lewis uses the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW) as an example to illustrate his point, noting that the “UAW’s strike fund alone, resting at approximately $826 million dollars, accounts for approximately 3% of the total assets reported by the entire movement.” This is an accurate observation, but taking a closer look at the UAW’s Strike and Defense Fund does raise some questions about whether these assets are as “restricted” as Lewis portrays, as well as his contention that using strike funds for other purposes (like organizing) is “raiding.”

The UAW constitution permits the Executive Board (the leaders indirectly elected by the members) to devote up to $60 million from the Strike and Defense Fund to “major organizing drives.” In fact, many union strike funds have a variety of democratic governance mechanisms that allow the elected leadership to use the funds for other legitimate purposes like organizing.

For example, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) constitution allows the funds to “support members engaged in collective action to obtain recognition,” the constitution of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) allows the executive board to transfer strike fund assets over $30 million to the general fund for any purpose, the United Steelworkers permits elected leaders to transfer assets from the strike fund to the general fund if it drops below $18 million, and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) allows the strike fund to be used for a wide variety of purposes, including holding “accountable national public officials for a pro-working family agenda.” The Communications Workers of America’s (CWA) Defense Fund co-mingles organizing and strike fund assets, providing some discretion to an oversight board to move assets.

When I worked for UNITE HERE, the union strategically (and democratically) moved assets back and forth between strike funds and key organizing campaigns (depending on, for example, the date of major contract expirations). This was not “raiding” of the strike fund, but elected officers using their discretion delegated to them through the union’s democratic governance mechanisms. Whether strike funds should be used for other purposes (like organizing) is open for debate, but these funds are far more fungible than Lewis suggests.

The UAW’s $826 million strike fund (the largest in the country according to my research) is an interesting case study. According to the data from the Department of Labor’s Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS), the UAW spent a total of $166 million on strike benefits over the last eleven years (2010-2021), or just 20% of the $826 million strike fund. This includes the six-week strike at General Motors in 2019 by 48,000 workers. Yet according to the UAW, the union only spent $10 million on organizing in 2020 (including $3.8 million diverted from the strike fund), or 1.2% of its assets and 5% of its revenues.

As union automakers continue to lose market share to non-union auto transplants like Toyota — and as union density declines in the motor vehicle and equipment manufacturing industry from 21% in 2010 to 13% in 2021 — UAW members might argue that a more coherent long-term strategy would be to increase expenditures to organize the non-union sectors by using a portion of the assets from the strike fund, rather than practicing an extreme version of Fortress Unionism. In fact, because the strike fund represents 75% of the UAW’s net assets (at the headquarters level), it is hard to see how the union will ever fund large-scale organizing without confronting this strategic choice.

As far as Lewis’ claim that a “significant percent” of union assets are devoted to strike funds, it is hard to arrive at a precise number because unions have, regrettably, opposed efforts by the Department of the Labor to require the disclosure of the amount of assets in strike funds (as well as the amount of expenditures devoted to organizing versus collective-bargaining). But we do know, as outlined in the report, how much unions have spent on strike benefits. Organized labor paid out on average $70 million a year in strike benefits since 2010, or just 0.35% of net assets annually. Over the last decade, roughly $767 million in strike benefits were disbursed in total, representing only 2.6% of the $29 billion in current net assets. If a “significant percent” of labor’s assets are devoted to strike funds as Lewis contends, unions are not spending those assets on strikes.

Despite the data in the report, Lewis also argues that the “assets available for strike pay are insufficient,” referencing his article Striking for Power, where he declares that “the biggest factor” determining whether or not strikes occur is “simple: money.” It is hard to reconcile that strong claim with labor’s $29 billion in labor net assets (up from $15.2 billion in 2010) and the relatively low strike activity over the last decade.

While the amount of money in strike funds is certainly one factor that explains strike activity (it certainly was not a factor in the massive Red Ed teacher strikes of 2018-2019), other factors that should be considered include the nature of the union’s contract demands and company proposals, the level of unionization at a company and its competitors, macroeconomic and labor force conditions, the competitive landscape and strategy of the strike target, the amount of internal organizing and education of the membership, and less savory, the symbiotic and clientelist relationship some (many?) unions have with their major employers (e.g. the corruption at the UAW). However, Lewis’ Striking for Power does offer a good analysis of the different ways unions could buttress their strike funds with more risk-sharing and solidarity (and one of the reasons I subscribe to his newsletter).

Apart from the UAW ($826 million) and Teamsters ($350 million) that Lewis cites, other large strike funds include the CWA ($432 million), and the Steelworkers (around $500 million by one account). For all strike funds where there is publicly available data (approximately $2.1 billion in total), that represents about 7% of net assets in 2020 (although preliminary 2021 data suggest net assets have risen north of $31 billion). Moreover, of the top twenty unions headquarters ranked by membership, eleven spent zero on strike benefits from 2010-2020. But for the sake of argument, let’s generously assume that real number of assets devoted to strike funds is 12% (or $3.5 billion) -- that still leaves $26 billion available for other purposes. Like strike funds, the remaining union assets may be “restricted” or designated for certain purposes, but they are subject to democratic control, and can be democratically redeployed for growth and worker power.

But I do agree with Lewis that strike funds are vitally important to defend workers taking the courageous step to call a strike against their employer. In the Teamster example, Lewis calculates that if there is a strike against UPS in 2023, the Teamster strike fund could potentially be exhausted in a month. While Lewis’ data is incorrect (there are 327,000 UPS members not 185,000, and roughly half the membership is part-time with different strike benefits), a month-long strike would cost UPS billions, not millions, and snarl an already overwhelmed supply chain network. In addition, the Teamsters have hundreds of millions of additional assets at the headquarter and affiliate-level that could buttress the strike fund. And like in 1997 when Teamster members struck at UPS for 16 days, other unions would (hopefully) stand by the strikers with financial pledges. As the Washington Post reported in 1997, “the AFL-CIO pledged $10 million a week to pay strike benefits for the UPS workers, and Sweeney said the federation had lined up more than $50 million in pledges from member unions by the time the strike had ended.”

C.M. Lewis versus John L. Lewis

Lewis is correct that the finances of unions are decentralized in hundreds or thousands of legal entities (how decentralized is another question that will be addressed in a future report), and that “the financial picture of some of those entities may appear significantly different.” Using UNITE HERE as one example, he notes the union was devastated by the pandemic, losing half its membership, and forced “to turn to liquid assets to fund the union’s continued operation, and that some fixed assets have been converted to liquid assets in order to stabilize their financial footing.”

I worked for UNITE HERE on organizing and contract campaigns for over fifteen years, so I am acutely aware of the impact of the pandemic on the union and its members. But there is another story. UNITE HERE devotes significant resources to organizing (up to 50% of the budget), and as a result, the union was one of the fastest growing unions before the pandemic, increasing membership from 229,823 in 2010 to 307,890 in 2019, or a 34% increase. That is more membership growth than many unions twice or three times the size. There were many explanations for the increase, but the union spent aggressively on organizing, consistently running operating deficits, spending more than the revenue it took in from membership dues. If all unions devoted 30-50% of their operating budget to organizing, and used their assets for growth rather than a version of Fortress Unionism, the labor movement would be in a much stronger position today (the good news, labor still can).

In contrast, compare the record of the National Education Association (NEA), one of the largest unions in the country (Lewis has been a staff representative for the Pennsylvania affiliate of the NEA since 2017 according to the OLMS data). Since 2010, membership has declined by nearly 300,000 members, yet the net assets of the union headquarters have increased from $160 million in 2010 to $348 million in 2021, or a 118% increase. Similarly, the UAW has seen its membership drop by 20% since 2007 (the year before the 2008 financial crisis devastated the auto industry), coupled with declining market share of the top 3 unionized automakers, yet has only spent on average 9.5% of its budget on organizing over the last three years.

While Lewis notes that some unions are doing well (financially) and some are not, the problem is that too many union budgets look like the budgets of the NEA or UAW, and too few look like the budgets of UNITE HERE (or other organizing unions like SEIU), and that is reflected in the aggregate data in the report. It is also true that the vast resources of organized labor are distributed unequally among a variety of unions and their affiliates.

To that point, Hamilton Nolan’s article forcefully argued that in this historical moment where so many trends are breaking in favor of workers and unions, we “need a movement that is moving in a coherent direction, towards progress. Instead we have a constellation of separate little groups all disclaiming responsibility for the big picture.” And similarly, veteran labor reporters Steven Greenhouse and Harold Meyerson have called this “Labor’s John L. Lewis Moment,” a time to deploy the union treasuries in support of a comprehensive organizing strategy — just as John L. Lewis did in the 1930s with the mineworkers treasury to form the Congress of Industrial Organizations. C.M. Lewis’ unfairly brands proposals like these as insufficiently cognizant of the complicated “federalized nature” of unions, and that urging elected labor leaders to develop a more ambitious organizing strategy is somehow an undemocratic “centralized imposition of union-wide priorities.”

Methodology and Data

Lewis dug into the methodology of the report, and he frequently uses data skillfully in his writing, so I appreciate his critique. I address the main points:

The OLMS data is “self-reported”: Lewis contends that the union financial data is “self-reported” (among other limitations) and should be heavily discounted as a result. However, unions are legally required to report the financial data to the Department of Labor. According to the statute, it is a crime (punishable up to a year in prison) to make “a false statement or representation of a material fact…in any document, report, or other information required under the provisions of this title.” In addition, the top officers of the union must sign the financial report and can be held “personally responsible” for false information. The Department of Labor provides very detailed instructions for filing the financial report, including software that most unions integrate into their accounting systems. Furthermore, the DOL has a team of investigators that audit the financial filings, and unions can face an intrusive investigation if the auditors uncover significant errors or false statements. Unions make honest mistakes in filing the report (and I occasionally find an error), and there is some room for interpretation of the reporting rules, but unions have a very strong incentive to provide accurate information.

Restricted vs Unrestricted Funds: Lewis contends that the report would be more useful if it employed non-profit accounting principles, segregating the financials into “restricted” and “unrestricted” funds. Restricted funds are monies set aside for a particular purpose (e.g. a strike fund) while unrestricted funds may be used for any (legal) purpose. The OLMS data does not provide that level of financial detail, and it is more typically found in a union’s internal budget document (which is rarely disclosed to the public). More importantly, it is a conceptual mistake to accept at face value that just because a union classifies some assets into a specific “restricted” fund (e.g a worker training fund), those assets cannot be democratically reallocated to another “restricted” fund (e.g. an organizing fund) or put into the general treasury. These financial decisions are subject to democratic control through specific governance mechanisms unique to each union, and as illustrated with the discussion about strike funds, far more common than portrayed by Lewis.

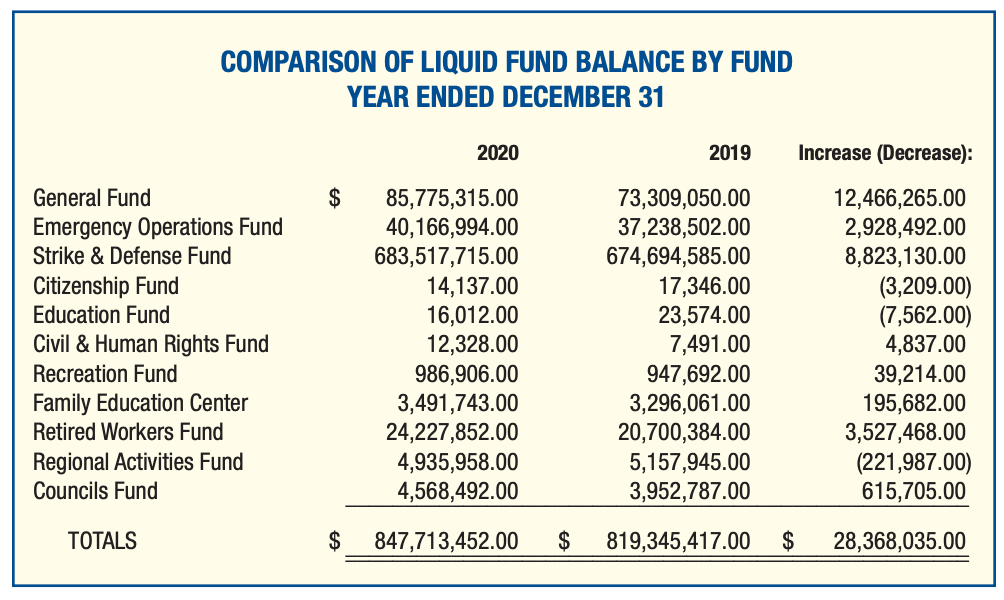

As an example, take a look at the “restricted” accounts of the UAW’s budget:

Under Lewis’ formulation, the UAW’s “Recreation Fund” or “Family Education Fund” are “restricted” assets and therefore unavailable for other uses like organizing. The only “available” assets -- under Lewis’ accounting framework -- are located in the General Fund, or just 10% of total assets.

There are some union assets that are truly restricted — for example, federal training funds that legally must be spent on specific programs — but these are a small portion of total assets.

Public Sector Unions: Another issue with the data that Lewis notes is that not all unions (such as those with exclusively public sector members) are subject to reporting requirements. As noted in the report, the DOL estimates it’s a relatively small number, but the other reason the data is missing is that public sector unions have opposed rules that require greater disclosure (including Lewis’ own union the NEA). While the reluctance of public sector unions to disclose additional information on their finances is understandable (given the utilization of the data by anti-union forces), it is ultimately a poor policy to oppose transparency and openness.

Different Reporting Cycles and Double-Counting: Lewis contends the data is potentially flawed because unions report on different cycles, and this could lead to double-counting. In the analysis of the data in the report, approximately 70% of unions report on a calendar year (with the rest of unions reporting on a fiscal year – e.g. July to June). This might be a problem looking at the data for just one year, but the report analyzed the data over a decade which should smooth out the impact of different reporting periods. In addition, most unions (headquarters and their affiliates/locals) typically use the same reporting period. In the example that Lewis provides, he suggests that SEIU headquarters and the SEIU Local 1199E could double count a small transaction because of different reporting periods. However, both unions report on a calendar year.

The AFL-CIO: Lewis criticizes including the AFL-CIO in the aggregate data in the report because the “AFL-CIO does not organize workers.” The AFL-CIO represents a very small portion of total union assets, and it is true that the AFL-CIO does not directly organize workers. However, the AFL-CIO has directly supported organizing campaigns by financing the hiring of organizers, researchers, communication staff, and other organizing infrastructure via affiliates. In fact I worked on some of those campaigns, including the United Farm Worker’s campaign to organize strawberry workers. In other writings, Lewis has argued that the AFL-CIO should be “pushing a worker agenda through worker organizing” so it is difficult to reconcile his criticism of the methodology with this statement.

But Lewis is correct that the OLMS data have some limitations (and five pages in the report are devoted to a discussion of these limitations and methodology). And I agree with Lewis that the report is not the “final word on the financial picture of organized labor,” and based on the feedback from some knowledgeable experts on the data, there is room for further refinements of the methodology.

Lewis proposed (in a series of tweets) that the AFL-CIO should take a role in mapping union finances at a national, state, and local level. This is an excellent idea and the data should be made public to all union members. As the Secretary-Treasurer of an AFL-CIO Central Labor Council in Pennsylvania, Lewis is in a position to make that happen (at least on a small scale).

Conclusion

Lewis contends in his article that before labor can pivot to an “actionable plan” on organizing, there needs to be “vast internal organizing and debate across the movement.” No one is against debate, but labor has been debating the need to organize for decades. Twenty-five years ago John Sweeney was elected to the leadership of the AFL-CIO after a vigorous public debate about organizing strategy (unlike the most recent AFL-CIO coronation convention). Sweeney set out real organizing goals for the affiliate unions, including a proposal that all unions devote up to 30% of their budgets to organizing. Many of the affiliate unions rebelled, and the goal was quietly shelved. Twenty-five years later and I would wager that only a handful of unions devote that level of funding to organizing (thanks to the practice of Fortress Unionism).

While calling for more sustained debate, Lewis also seems (at times) to entirely write-off organizing by traditional unions. In his defense of AFL-CIO president Liz Shuler’s tepid goal of organizing one million workers over the next ten years, Lewis writes that “staff-driven approaches simply cannot scale up adequately, no matter how many centers are created and how many dues dollars are thrown at the problem.” Instead, Lewis writes that the “Workers United [Starbucks campaign] is possibly the only union programmatically embracing the sort of organizing necessary to hit or surpass Shuler’s goal.” The “only” union and the “only” sort of organizing?

The independent worker movements (like those at Starbucks, Amazon and a growing list of other companies) are one of the most exciting developments in the labor movement, but traditional unions still have a very large role to play in reversing the decades-long decline of union membership and power. Existing unions can organize on a large scale if they devote the necessary resources (while supporting independent unions and other organizing experiments), utilize organizing best practices like member-to-member organizing, and embrace experimentation and challenge orthodoxy. Within every labor union there are devoted organizers and staff (many from the rank-and-file) pushing for more ambitious organizing campaigns, and many of those organizers would say they could do far more organizing if they had the resources. It is one of the reasons I wrote the report.

Labor can keep debating the issue (as they have been for three decades), but this unique window of opportunity for action will soon close. That would not only be a crisis for the working class, but a crisis for democracy itself.

Housekeeping

This is the first issue of the Radish Research newsletter, which will occasionally look at labor movement issues that are not typically reported or covered. You can read my bio here, and learn why I call my one-person consulting firm Radish Research.

Looks like the link to your report itself is broken….