Labor's Net Assets Rise by $3.5 billion in 2021 while AFL-CIO Pledges "Unparalleled Investment" in Organizing

The Department of Labor’s data of union financial filings is now available for 2021, so I’ve updated my report on labor finances with the new data, as well as made some tweeks to the methodology.

The good news from the financial analysis is that organized labor as a whole continued to grow net assets and surpluses in 2021; the bad news is that, well, unions continue to grow net assets and surpluses rather than boosting spending on organizing and strikes. Perhaps the recent announcement by the AFL-CIO that it will make an “unparalleled investment” in organizing will finally move the needle?

2021 Assets, Revenues and Spending by Unions

As Table 1 below shows in 2021 the net assets (assets minus liabilities) of unions grew by $3.5 billion since 2020, rising from $28.1 billion to $31.6 billion. Since 2010, net assets have more than doubled — all while union membership declined by over 700,000 members.

Table 1: Labor’s Balance Sheet

Net assets primarily rose in 2021 because, as Table 2 shows, unions booked a $2.5 billion surplus, up by $215 million from 2020. While membership declined by 246,000 members in 2021 compared to 2020, total union revenues increased by 1.6% and spending only increased by 0.4% in 2021.

Table 2: Labor’s Income Statement

Unions did reduce their spending in 2021 in several categories, including political spending (off election year), contributions and grants, and overhead and administration. And according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, unions continue the long trend of reducing staff.

As Chart 1 illustrates, unions reduced employment by 1,100 staff in 2021, or a -0.9% reduction, while the median wage rose 2.4% in 2021 to $74,180. Yet management occupations rose by 37% from 9,390 positions in 2020 to 12,040 in 2021. Organized labor appears to be getting more top heavy, and if you’ve worked for a union, this is probably not breaking news.

Chart 1: Union Employment and Compensation

Still it is baffling that unions continue to reduce staff while revenues and assets exponentially increase. One explanation is that a number of smaller unions and locals have either been terminated or merged into larger unions, leading to staff layoffs. Since 2010, the number of unions filing LM reports with the DOL has declined by 17%, or over 4,800 entities.

Unions have increased spending by $2.3 billion since 2010 (still far below the growth of revenues), but this spending has not translated into staffing increases to make up for reductions due to mergers and terminated locals.

Strike Benefits and the NFL Strike that Didn’t Happen

I was curious to see that strike benefits (Table 3) paid by unions increased substantially in 2021, rising from $50 million in 2020 to $170 million in 2021, the highest payout in a decade.

Table 3: Strike Benefits — 2010-2021

But digging into the data (with some help from a knowledgeable colleague) provides an explanation for the increase in strike benefits. The NFL Players Association reported spending over $54 million on strike benefits in 2021. I’m not a football fan (go Orioles), but I sure don’t remember a football strike last year.

Buried in the footnotes, the NFL Players Association explained why they reported $54 million in strike benefits in their LM-2 filing.

“a Work Stoppage Fund was established to financially assist qualifying players in the event of a breakdown during CBA negotiations resulting in a work stoppage. Qualifying players contributed their annual earned royalty for the 2017 and 2018 seasons as supplemental dues to the Association. A new CBA was approved in March 2020. As such, the work stoppage fund was disbursed to those qualifying players…”

So the real number of strike benefits paid in 2021 is more like $116 million if you exclude the phantom NFL benefits.

The AFL-CIO’s “Unparalleled Investment” in Organizing?

Dave Jamieson at HuffPost broke the story that the AFL-CIO Executive Board approved a per capita increase (the amount affiliate unions pay to the AFL-CIO) to raise $10.8 million for an organizing fund. Liz Shuler, the President of the AFL-CIO, said the fund was an “unparalleled investment dedicated exclusively to organizing to build power for America’s workers seizing this unprecedented moment.” I love an unparalleled investment as much as the next person, but let’s look at the financials from the Department of Labor to put it in perspective.

Chart 2: AFL-CIO Spending 2011-2023(E)

The $10.8 million in the new organizing fund would increase the AFL-CIO’s total spending (at the headquarter level) in 2023 to $105 million (all things being equal), up from $94 million in 2022, or a 12% increase. But as Chart 2 illustrates, the new projected spending is far below what the AFL-CIO was spending as recently as 2017. In late 2017, the AFL-CIO laid off dozens of staff as part of a restructuring, inaugurating a period of reduced spending by the federation going forward (Shuler was Secretary-Treasurer during this time). In 2019, Hamilton Nolan reported on a leaked AFL-CIO budget that showed that the federation was spending less than 10% on organizing in 2019, down from 30% a decade ago. So it looks like the AFL-CIO’s “unprecedented” investment in organizing does not even approach the levels of investment a decade ago.

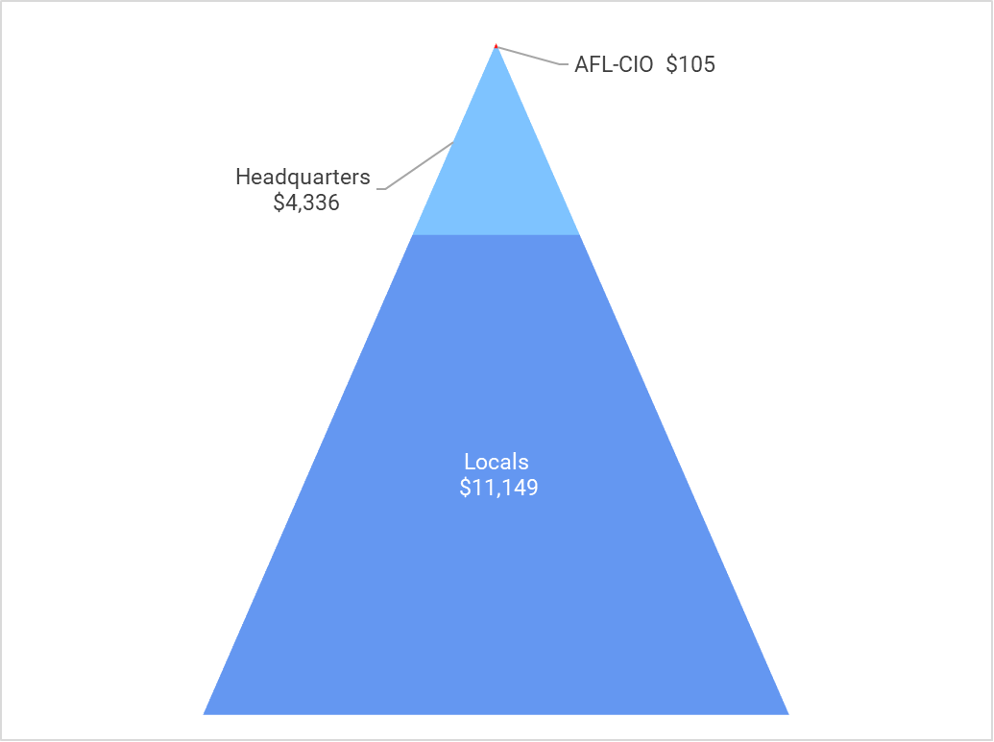

There is also a misconception among some that the AFL-CIO headquarters is a large entity with significant financial resources. But as Chart 3 illustrates (if you use a magnifier), the total projected spending of the AFL-CIO is miniscule — 0.7% — compared to spending by union headquarters and their local affiliates.

Chart 3: AFL-CIO Spending vs The Rest of Organized Labor: 2021 ($millions)

The $10.8 million organizing fund is also far less than the federation spends on politics: $23 million in 2022 (fiscal year ending in June 2022) and $37 million in 2021. Norm Scheiber, the New York Times labor reporter, wrote an excellent piece on the competing visions of the AFL-CIO. Should it focus on politics and lobbying or “play a leading role in building the labor movement — by investing resources in organizing more workers”? Shuler comes out of the first camp, spending her career almost exclusively working on political campaigns (I can find no reference in her biography of ever leading an organizing campaign). But clearly the new-ish leadership is going to try and straddle both camps with the limited resources of the federation.

Nevertheless, it is mildly encouraging that the AFL-CIO is increasing spending by about 12%, and perhaps something interesting will emerge from the experiment. But if all of labor followed the lead of the AFL-CIO and increased spending on organizing by 12%, we would be taking about $1.9 billion in new spending — now that would be “unprecedented.”

Methodological Update

Thanks to the many people who’ve written with questions and comments about the methodology and substance of my report on labor’s finances. As a result of these conversations, I’ve made an adjustment to the methodology, only analyzing unions that file a Form LM-2 (unions with $250k or more in annual receipts) while excluding the very small unions that file a Form LM-3 (receipts greater than $10k and less than $250k). This change barely impacts the overall financial numbers because 97% of union assets are held by LM-2 filers, but it does relieve some of the database burdens on the staff of Radish Research (that would be me). I’ve left a copy of the old report on the website if you want to compare it to the updated and revised report.